Positive Health Online

Your Country

Spring Walker - Excerpt from Born to Walk

listed in anatomy and physiology, originally published in issue 268 - February 2021

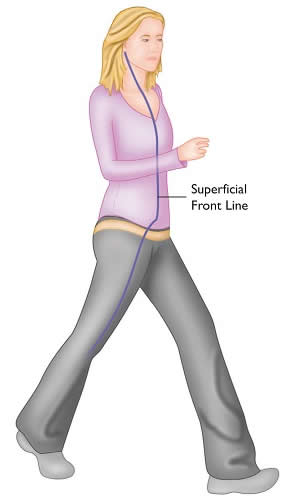

Republished from Born to Walk – Myofascial Efficiency and the Body in Movement 2nd Edition by James Earls

Reviewed in PH Online

“Did man possess the natural armour of the brutes, he would no longer work as an artificer, nor protect himself with a breast-plate, nor fashion a sword or spear, nor invent a bridle to mount the horse and hunt the lion. Neither could he follow the arts of peace, construct the pipe and the lyre, erect houses, place altars, inscribe laws, and through letters and the ingenuity of the hand hold communion with the wisdom of antiquity, at one time converse with Plato, at another with Aristotle, or Hippocrates.”

–– Galen

The effectiveness of our bipedal gait has been honed and matured by evolution over the last 4 million years. Walking on two legs was something of a compromise of mobility over stability, because, by standing upright, we put our lower backs and sacroiliac joints at some peril, but the advantages must outweigh these occasional sacrifices.

Coming onto two legs may have decreased our exposure to the sun, and it certainly freed our arms for the control of tools and, eventually, fire. It is metabolically cheaper, allowing us to scavenge further from our home base. The development of running, and therefore persistence hunting, may have coincided with the capacity for abstract thought – being able to visualize and predict the movement of the hunted animal. Cooking the meat over the fire and sharing thoughts about the hunt (and then embellishing stories about it) – along with the cooperation necessary for the hunt itself – may have helped expand our early language.

All of these factors added to our adaptability and made calories more available to us. We have had larger, stronger, and bigger-brained cousins as ancestors, but we are the ones still around. As the dinosaurs learned – at their cost – bigger is not necessarily better. Our brawnier cousins, the Neanderthals, died out as well. They were sturdier and stronger than Homo sapiens, but probably required more calories to survive and presumably were not as agile.

Soft tissues are rarely, if ever, preserved in the fossil record, so we have no way of knowing exactly the difference between our elastic tissue and theirs. But judging from the solidity of Neanderthal bones and those bones’ growth patterns and the insertion points, it seems clear that our lighter frame benefits from our fascial system. Our upright stance allows us to load the fascial system through gravity and through forward, backward, lateral, and rotational movement. We benefit from our unstable vertical alignment by letting it challenge and stretch the elastic tissues throughout the body, loading them with energy that we then use for movement, most commonly for walking.

Our survival, however, has been dependent on so much more. With just the minimum tools in terms of muscle power and strength, we have maximized our diversity. While Homo sapiens will never outrun a cheetah, lift more weight than a rhino, or swim faster than a dolphin, it is a fact that we can perform all of these activities. No other animal has mastered such a wide range of motion in such a variety of different environments.

Our versatility is unmatched, and we do most motions (once practiced!) with grace, with an ease that is the hallmark of fascial efficiency. As Fukashiro (2006) states, “Most dynamic movements in sports activities involve a countermovement, where an agonist muscle contracts after being stretched in an eccentric phase, which is usually defined as a stretch shortening cycle.” Essentially, by going in the direction opposite to the one we want to travel in, we are using the efficient dynamics of the stretch-shortening cycle, which is “the natural way of muscle function in normal locomotion … nature’s way to combine the available resources … in such a way that both peak performance and movement economy are considered in the most appropriate way in each particular movement situation” (Komi 2011).

When we match joint alignment with the pull of gravity and the ground reaction force – coupled with the momentum involved in any movement – we can see how the dynamics are channelled into the elastic tissues. By exploiting the instability of our vertical alignment and smooth joints, we easily gain countermovement. The mechanoreceptors embedded within our wonderful three-dimensional web of fascial tissue activate the necessary muscles to decelerate the action that stretches the elastic fascial tissue, which can assist the recovery movement with metabolically “free” energy.

When we look at Muybridge’s horse progressing from a trot to a gallop, we see increases in flexion and extension, the greater movement putting more load into the tissues to support and produce the stronger forces required. The quadruped is more clearly a full-body walker; the quote that began this book shows that we have yet to appreciate the full involvement of our anatomy in locomotion, since half of it is sadly labelled the “passenger” (Perry and Burnfield 2010).

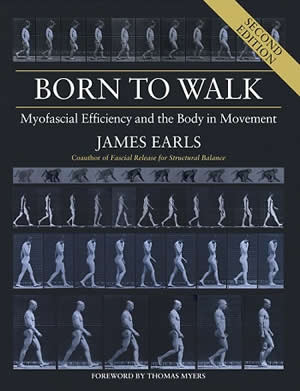

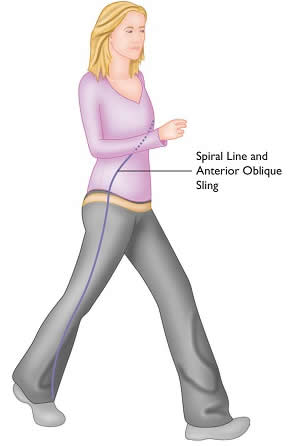

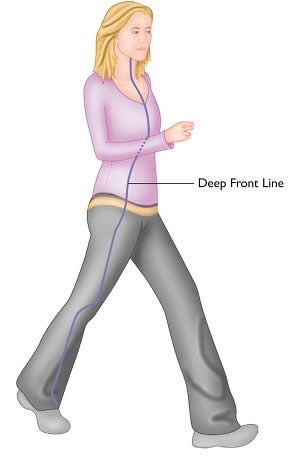

I think it is an interesting exercise to take the two transition points – heel strike and toe-off – and reverse engineer them by simply looking at where the forces are traveling. At toe-off, we have progressed our pelvis forward from the back foot to create a line of tension along the entire front of the body [Figs. 8.1–8.9].

Figure 8.1. The continuity of the SFL - Superficial Front Line - is challenged but the toe-off position strains much of the anterior tissues, especially the vertically aligned muscle fibres. By going into extension, we have put kinetic energy into many of the flexors, to be released at toe-off.

Figure 8.2. At toe-off, the toe extension and knee extension have strained the lower leg.

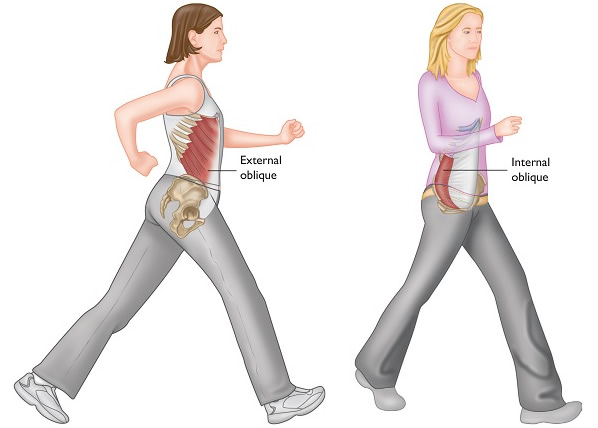

Figure 8.3. The counterrotation of the shoulder girdle creates the tension through the oblique tissues.

Figure 8.4. The combination of dorsiflexion, knee extension, hip extension, abduction, and internal rotation is the ideal position to lengthen the Deep Front Line, which will assist with almost all the required events at toe-off.

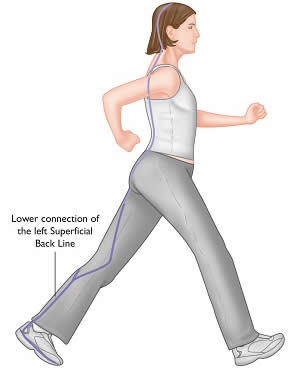

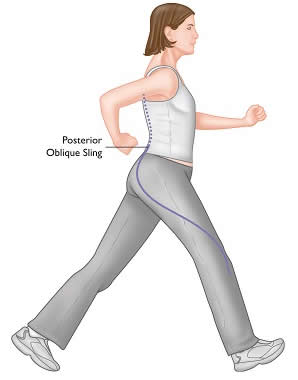

Figure 8.5. At heel strike, the flexed hip position will require support from all of the hip extensors.

They will be in a pre-tensioned position because of the flexion, and Vleeming’s Deep Longitudinal Sling

may assist with sacroiliac stability after heel strike.

Figure 8.6. At heel strike, we can follow the rotational forces caused by the tilt of the calcaneus to bring us to the superior portion of the gluteus maximus from the tibialis anterior and the ITB. From there, we carry into the latissimus dorsi to create a form of sling (as used by Zorn and Vleeming). This superficial sling addresses the rotational aspects of the pronation pattern, while the Deep Longitudinal Sling helps balance the sacroiliac joint through the connection to the sacrotuberous ligament and the long dorsal sacroiliac ligament on the opposite side.

If we look back to the work of Huijing, mentioned in Chapter 1, in which he examined the transfer of force from one tendon into the surrounding tissue, we can now really appreciate the complexity and beauty of the myofascial arrangements. Working as a separator, connector, force concentrator, force damper, and force-dispersal system, the myofascial system not only communicates mechanical information directly through its fibres but also senses and adjusts the sectional stiffness according to the forces acting at any one time.

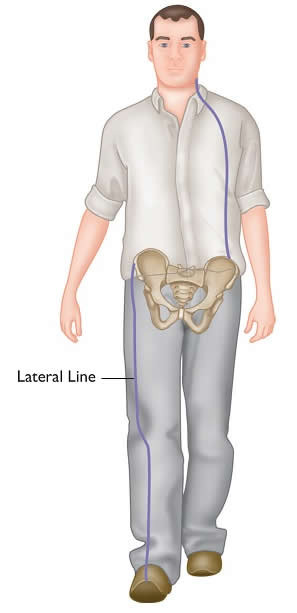

Figure 8.7. With the center of gravity at the midline of the body offset from the point of support, the hip is encouraged into adduction on the side of heel strike, which loads the hip abductors on that side. Meanwhile, the hip adductors, lateral abdominals, and quadratus lumborum must open on the opposite side.

Footwear

Nature, Mr Allnut, is what we are put in this world to rise above.

—Rose Sayer (played by Katharine Hepburn) in The African Queen

One of the most obvious ways we try to rise above nature is through adornment, and, when not passing our time inventing new methods of maiming and killing each other, humanity has often diverted its attention to novel ways of mutilating the body we inherited. From foot binding to winkle pickers, stilettos to platform boots, each generation and each culture has managed to find a way to interfere with the natural dynamics of our feet. When left to their own devices, our feet serve us quite well, and they really need little more than some protective covering to save us from the vagaries of litter and sharp (or sometimes squidgy) objects.

Figure 8.8. With the pelvis moving further and faster than the rib cage, the Xs of the lateral abdominals will be stretched in opposite directions on each side. These “ipsilateral” obliques therefore carry the rotation created by bipedal gait into the intercostals – this is damped by counterrotation of the arms and “contralateral” obliques (see Fig. 8.3).

Figure 8.9. As the leg swings through into hip flexion, the adductor magnus on the swing leg will be lengthened, in order to pre-tension it prior to heel strike, when it will work to resist further flexion. During the swing phase, it may help to tension the deep posterior compartment fascia to supinate the foot prior to heel strike.

Hopefully by this stage of the book, enough evidence of the interaction between anatomy, function, and evolution has been presented to convince you of their interrelationship.

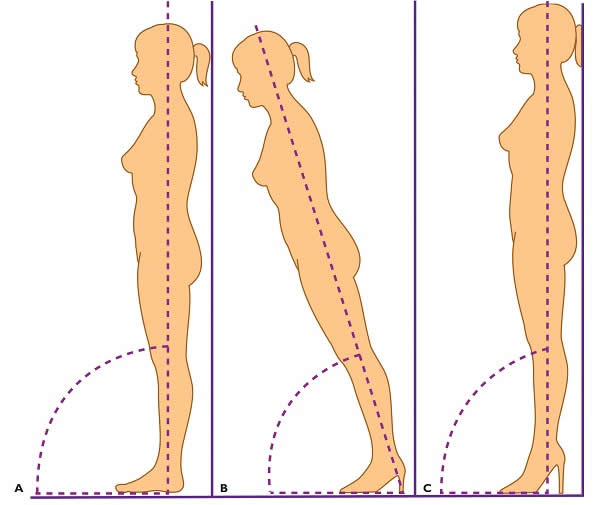

So, with apologies to Miss Sayer, we would be better served by not trying to rise above our nature, at least in the foot department. A thick sole will dampen our proprioceptive feedback (Saxby 2011). An elevated heel will force more of the body weight onto the metatarsal heads, stressing them, and it will shorten the Achilles tendon, distorting the posture and interfering with the communication through the lines. An elevation of two inches will give the body an incline of 20 degrees, leading to a 23 percent increase in the load on the front of the knees. A three-inch heel puts 76 percent of the body weight on the metatarsal heads, which are not designed for that kind of constant stress (see fig. 8.10).

Figure 8.10. A to B, When adding a heel to a neutral body, the incline created by the heel has to be compensated for somewhere in the body: at the knee, the hips, the lumbar spine, or the thoracic spine, depending on one’s tendency. This places undue stress on any or all of those areas, increasing the likelihood of pain and dysfunction. C, As the heel increases in height, an ever-greater percentage of body weight is brought to the ball of the foot, decreasing efficiency and increasing stress on the bones. (Adapted from Dalton 2011.)

Cramped toe boxes lead to misalignment of the first and fifth toes (predominantly, though in many cases the others can be affected as well), which leads to varied angles at toe-off (see fig. 8.11). This can be further exacerbated by the longitudinal axis of the shoe, which is often curved, especially in athletic shoes.

A shoe is not only a design, but it’s a part of your body language, the way you walk. The way you’re going to move is quite dictated by your shoes.

—Christian Louboutin

For a normal foot, the ideal shoe would be flat (see fig. 8.11B). Wearing a minimal sole allows clear proprioception, but it should be thick enough and strong enough to offer protection. A wider toe box gives the toes room to spread on contact with the ground, which is mechanically useful. As the metatarsals spread, the interossei will be stretched, signalling a reflex contraction of the quadriceps (Michaud 2011). A simple arrangement of the shoe, one in which the alignment of the foot is unaltered, is ideal. It will allow the joints to work through their normal range, loading the appropriate tissue through the progression from heel strike to toe-off.

Figure 8.11. The ‘normal’ shoe (A) has many supposedly positive features. Running shoes, in particular, may include “motion control,” extra heel cushioning, and a curved longitudinal axis. Some of these features may be necessary for challenged feet, but they will interfere with the natural architecture and function. Thicker soles dampen proprioception; motion control, strangely enough, prevents motion, which also lessens proprioception communication through the body and inhibits some of the normal tissue responses described in this book. The cramped and angled toe box will affect the foot’s ability to spread and then push off at an optimal angle. A minimal shoe (B) simply provides protection from the elements and unseen objects. The thin and pliable sole allows the foot to feel the ground and make appropriate responses, while the wide toe box and lack of curving from heel to toe facilitate actions of the metatarsals, from the spreading at heel strike to the correct angle at toe-off.

Anything that interferes with joint alignment will affect our ability to use the longer springs of the body. Wearing high heels not only places more weight on the metatarsal heads but also prevents the ankle from dorsiflexing, while cramped or angled toe boxes will force toe-off to occur at angles other than the ideal first and second metatarsal heads.

Various ‘fitness’ and ‘technology’ shoes have appeared on the market over the last ten years – many making health and beauty claims. One of the reasons why they claim to “help you lose weight,” “burn more calories,” or “give you long lean legs” is the fact that they alter the body’s natural mechanics. We have evolved to make walking as easy and as calorie efficient as possible, so by interfering with that process, we have to compensate with muscle work. When we do so, however, we are also at threat of changing the forces that flow through the joints, making these “technology” shoes unsuitable for many people, if any.

Most shoes are shaped as if feet were made for shoes.

—Mokokoma Mokhonoana

Many people, because of inherited characteristics, accidents, or misuse, no longer have the ideal alignment through the joints of the feet. They may benefit from the use of orthotics to retain efficiency. I believe orthotics to be an intervention of last resort, preferring to use manual therapy, manipulation, and/or exercise to normalize the foot as much as possible. If orthotics are to be used, they should be expertly fitted, and the client should be monitored by an experienced clinician to assess the rest of the body’s adaptation to the orthotics. Too often, orthopaedic insoles are prescribed, and then the job is considered done. The body will require time, however – and possibly some assistance – to recognize the new position it is in, and so a full screening of the “essential events” should be repeated.

I have two doctors, my left leg and my right.

—G. M. Trevelyan

But the beauty is in the walking – we are betrayed by destinations.

—Gwyn Thomas

Further Information

Available from Lotus Publishing, Amazon.co.uk and Amazon.com

Comments:

-

No Article Comments available