Positive Health Online

Your Country

New Perspectives on Back Pain – The Suffering We Share

listed in back pain, originally published in issue 271 - June 2021

New Perspectives on Back Pain – The Suffering We Share

by Robert Schleip PhD MA

Chronic back pain is something many of us now suffer from and one of the most common causes of disability and early retirement. And yet, we still have no adequate explanation as to what causes it. The usual suspects are intervertebral discs, vertebrae, nerves or weak and incorrectly exercised muscles. Only very rarely do disc and vertebral operations lead to permanent improvement. Conversely, there are many people with visible intervertebral disc and vertebral damage who have no symptoms or pain. Muscle strengthening does not always help – even well-trained athletes can suffer from back pain.

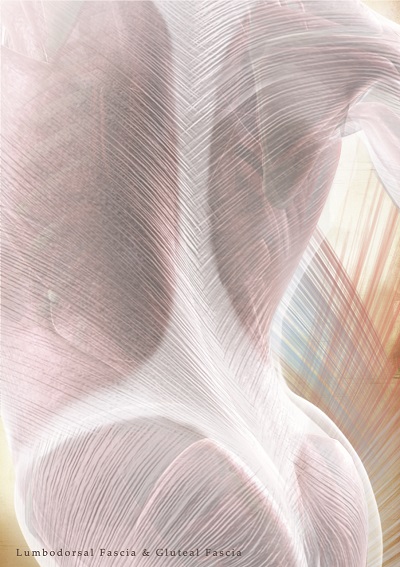

Fascia research is shedding new light on the problem. Firstly, we have learned that the fascial tissue is densely populated with pain sensors, especially in the back. We then saw that, because the large lumbar fascia contains many contractile cells, it contracts under the influence of certain substances and under stress. Studies carried out on male patients with back pain have shown that their lumbar fascia, the large fascia in the lower back region, is significantly thicker. This entire area is highly sensitive to pain, and patients tend to have a characteristic way of walking. All this suggests that disorders or problems in the fascial tissue in the back contribute to pain, or that these issues might even arise there. Small wounds or fractures in fascia caused by irregular and one-sided strain may play a key role. Such micro-injuries to the fascial tissue could cause inflammation, as well as false signals, which are then transmitted from the fascia to the muscles. The subsequent muscle disorders cause further cramping, and both of these together could lead to chronic back pain. This has given rise to researchers all over the world continuing to investigate the role of fascia in the generation of pain.

Recently, researchers in the United States have shown that lack of exercise, as well as tiny injuries to the tissue of the lumbar fascia, both play an equal part in this large fascia becoming matted. Doing less exercise may in part be due to the patient’s attempts to avoid the pain, as people tend to move less when they are worried about pain. It’s bad enough if the back fascia is affected by just one of these two issues – if you’re something of a chronic couch potato, for example – but things get really bad when both of these factors come together. So the long and the short of it is: if you have back pain, you should definitely keep moving. Otherwise you are at risk of severe matting in the large lumbar fascia, which takes a long time to undo.

Another finding of the fascial research into back pain is that the pain deep inside the back that starts in the fascia has a very particular characteristic, in that patients often describe it as being ‘nasty’ or ‘horrible’. People tend not to attribute these sorts of emotional attachments to muscle pain.

Lumbodorsal and Gluteal Fascia, Courtesy © fascialnet.com

We also have a new understanding of how this large back fascia is structured. Researchers in the US recently found that it is made up of three different layers. The top two layers closest to the skin are actually tensed by different muscles, despite being very closely interlinked – so they slide against each other only a very minimal amount. The first of the two layers is a core component of the functional fascial line in the back, while the second is part of the large dorsal line. These findings have already impacted the exercises athletes do to prevent back problems. These days, we not only work out the back muscles themselves, but also include exercises that use the arms. The aim of this is to create an active network of tensile stress between the arms and legs and across the back, which stimulates this important layer of fascia.

The third and deepest of the three layers of fascia in the back is connected to the abdomen and thus the abdominal fascial network. This is tensed by the innermost abdominal wall muscle, which in turn is closely linked to the pelvic floor and the diaphragm. This new anatomical finding shows that exercises which stabilise the core – such as those used in Pilates – could be the ideal solution to back pain.

The exercises in this book incorporate these new findings about the deep layer of lumbar fascia and its connection to the abdomen, and you will find that some now include the pelvic floor and diaphragmatic breathing. You will learn about these in Chapter 3.

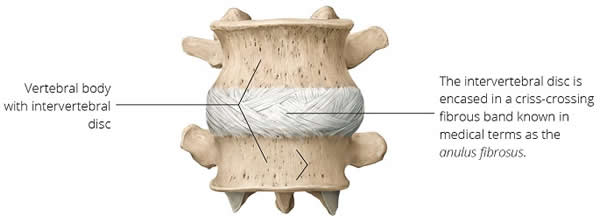

The intervertebral discs between the vertebral bodies are clearly designed to account

for the fact that the vertebrae are often twisted against one other,

because the protective band around them is made up of criss-crossing fibres.

For now, I’d like to mention more about the intervertebral discs. While they often have the finger of blame pointed in their direction, they are actually only to blame for around 15 percent of back problems. And even if the source of the pain genuinely is a herniated or slipped disc, the fascia is in fact partially responsible. That is because the intervertebral discs are encased in a fibrous sheath, which is what holds them in shape. This sheath, referred to in the medical world as the anulus fibrosus, is a layer of tissue made up of cartilage and fascial connective tissue, and contains a high proportion of collagen. In healthy people, its fibres are arranged in a criss-crossing pattern, running diagonally to the axis of the body. Based on this, fascial experts have been able to conclude that the torso, along with its ligaments and vertebrae, is naturally configured to perform rotating movements – i.e. to rotate and twist around its own axis. One issue is that people nowadays tend not to get enough exercise, but particularly that they only perform a very limited repertoire of movements as part of their day-to-day life. This could be one reason for the degeneration of the fascial sheaths between the vertebrae. If the sheath around the vertebrae tears, the intervertebral disc pushes out. This is what is known as a herniated or slipped disc. Fascia researchers and therapists therefore believe that, in order to be effective, any training intended to prevent back pain must also include rotational movements such as barbell torso twists or oblique sit-ups. The twisting versions of the flamingo, throwing and elastic jumps exercises, which you will find in the next chapter, are ideal for this.

Acknowledgement Citation

Extracted From Fascial Fitness – How to be Energetic, Elastic and Dynamic in Everyday Life and Sport, Second Edition by Robert Schleip

Published by Lotus Publishing. 2021. £14.49 / $24.95. ISBN 978 1 913088 21 7.

Available from Lotus Publishing, Amazon.co.uk and Amazon.com

Comments:

-

No Article Comments available