Positive Health Online

Your Country

The Osteopathic Approach to the Temporomandibular Joint (TMJ)

listed in osteopathy, originally published in issue 128 - October 2006

Summary of Anatomy and Motion Review

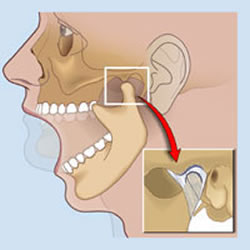

The Temporomandibular Joint (TMJ) consists of the head of the mandible and mandibular fossa of the temporal bone. A fibrocartilaginous articular disc separates these two structures. The stylomandibular ligament connects the angle of the mandible to the styloid process of the temporal bone. The sphenomandibular ligament connects the lingula (medial aspect) of the mandible to the spine of the sphenoid (Ermshar, 1985).[1] When the mouth is opened, the head of the mandible and articular disc move anteriorly on the articular surface of the temporal bone, while the head of the mandible rotates on the inferior surface of the articular disc around a transverse axis (Kapandji, 1970).[2] During protraction and retraction, the heads and articular discs slide anteriorly and posteriorly respectively, the temporalis, masseter and medial pterygoid muscles close the mouth, with a combined pressure of 96 kg or 200 lbs. The mandible is protracted by the lateral pterygoid muscle and retracted by the posterior fibres of the temporalis muscle. Gravity normally opens the mouth, and is assisted by the lateral pterygoid (which has an attachment to the intra articular disc), suprahyoid and infrahyoid muscles. All the muscles of mastication are innovated by the mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve.

Assessing TMJ Restriction

Frequently, the anterior gliding motion of the mandible and articular disc is restricted. Assume that the patient has a left TMJ restriction. As the mouth opens, the right side of the mandible and right articular disc glide anteriorly while the left side is restricted. This results in deviation of the chin to the left side (the side of restriction). Cranial dysfunction may affect TMJ motion. As the temporal bone externally rotates, the mandibular fossa moves posteriorly and medially. Internal rotation allows the mandibular fossa to move anteriorly and laterally. The mandible may deviate toward the side of the externally rotated temporal bone, or away from the side of the internally rotated temporal bone. Sphenoid dysfunction may affect the TMJ through its direct articulation with the temporal bone or by its articulation with the mandible through the sphenomandibular ligament (Pinto, 1962).[3]

TMJ and It's Effects Upon the Body

Short leg syndrome has also been associated with TMJ, via pelvic torsion and the resultant functional scoliosis that terminates in the cervical spine, thereby unbalancing the stomatognathic system (Walther 1983).[4] This system incorporates the head, neck and jaw. It includes the hyoid bone and the muscles connecting it to the manubrium, mandible and scapula, and it includes the facial sheets within the anterior cervical region, as well as other structures in the neck.

Walther, an American chiropractor, first discussed the inter-relatedness of parts within this system. He first showed the way that many of the muscles in this region act in a dynamic balancing manner. The efficiency of this balancing system contributes to the effective function of the mouth, throat, cervical spine and head, as well as the thorax and upper extremities.

This system of balancing muscular action means that the orientation of the cervical column could as much be influenced by combined tensions within these muscles.

The Temporomandibular Joint, Hyoid Bone and Sternal Relationship

The hyoid is uniquely placed to monitor the diverse patterns of tension that can arise through its system of muscular soft tissue attachments during everyday activity (Moore 1992).[5] Via the stomatognathic system, the hyoid links the scapula manubrium mandible and cranial base. The hyoid is also attached to the pharynx (in which the Eustachian tube and pharyngeal tonsils are embedded) and the tongue.

Any torsion within this area will have consequences for the anterior cervical fascia and the thyroid gland, and also for pharyngeal, Eustachian tube, tongue and temporomandibular joint mechanics. They will also distort the proprioceptively feedback essential for the control of the whole body posture. Hence the stomatognathic system should be viewed as a part of the balance control systems for the whole body, and should be assessed during examination of this area. As dysfunction in one area (i.e. one TMJ) can have a widespread effect on the balance of the entire area (Kuchera, 1994).[6] Thus, osteopathic intervention can be of great help in returning to balance this area.

Typical Symptoms of the TMJ Sufferer

|

Causes of TMJ Pain There are many theories about how most TMJ syndromes occur (trauma, grinding teeth, malocclusion syndrome (bad bite), too much hard chewing, stress). There is little scientific consensus on how the syndrome occurs and even less on how to treat it effectively. Most of these syndromes develop over time with the onset of symptoms; often years after the actual problem began. Primarily muscles control the joint and the syndrome is often a secondary effect of muscular dysfunction. |

| Osteopathic Treatment for TMJ The TMJ is a muscular joint and muscular dysfunction within the joint may cause the jaw to deviate from its normal alignment. Theoretically, the joint will stay in proper alignment and should work well if any muscle imbalance is corrected (ie. by ensuring both sides of the jaw are of equal length, to prevent uneven pulling of the jaw muscles). Various osteopathic techniques help to restore normal muscular function without the use of drugs, splints or surgery. |

|

Advice

|

|

Evaluation

Dysfunction of the TMJ can be broadly classified into three groups:

Developmental Abnormalities

• Hypoplasia (under-development;

• Hyperplasia (over-development);

• Boney impingement of the coronoid process;

• Chondromes;

• Ossification of ligaments (Eagles syndrome).

Intracapsular Diseases• Degenerative Arthritis;

• Osteochondritis;

• Inflammatory arthritis (rheumatoid, psoriatic and gout);

• Synovial chondromatosis;

• Infections;

• Metastatic tumours.

Dysfunctional Conditions (Most Common)

• Altered bite malocclusion, due to ill-fitting dentures, poorly filled teeth, raised crowns missing/removed teeth, especially molars, etc;

• Muscular imbalance;

• Capsular strain, due to trauma;

• Excess chewing (especially gum), teeth grinding, stress;

• Hypo/Hypermobility;

• Disc displacement;

• Disc adhesion;

• Trauma to the mandible (RTA, Blow, Fall).

Dysfunction, Observation, Examination and Diagnosis

Inspect the face and jaw, looking for asymmetry, misalignment of teeth and evidence of swelling. Ask the patient if the movements are painful. Normal opening should accommodate three of the patient's fingers inserted between the incisors. If not, hypo-mobility resulting from joint dysfunction, or a closed lock as a result of disc displacement, should be suspected. If opening beyond three fingers occurs, hyper-mobility from ligament laxity (previous trauma) or capsular overstrain is likely (Farrar & McCarty, 1983).[7]

Also, palpate the muscles of mastication to determine changes in tone, texture and tenderness. Temporalis and masseter can be reached externally. Medial and lateral pterygoids, intra-orally.

Dysfunction: Diagnosis

Placing gloved thumbs can assess the accessory motions of the TMJ intra-orally over the lower teeth, and wrapping the fingers around the mandible externally. Apply passive stress to A-P glide and lateral glide. Normally a springing end feel is perceived.

General observation of the mouth should be performed to rule out dental or oral lesions. Also, you can ask the patient to close the teeth quickly and sharply. This should not be painful, and a broad clicking of the teeth should be heard. If pain or only a single strike is heard, it would indicate a tooth abscess or malocclusion (Kraus, 1987).[8] Referral to a dental practitioner is advised.

Place your hands on either side of the patient's head with your index fingers anterior to the external auditory meatus (area of the TMJ). Instruct the patient to 'open the mouth slowly'. Observe the chin (or midincisural line) for deviation from the midline while palpating the TMJs. Remember that deviation occurs to the side of the restricted TMJ. If there is also an audible 'clonk' it indicates that the lateral pterygoid has shortened, pulling the articular disc into a position of mechanical disadvantage, resulting in the condyle riding over the disc (Wadsworth, 1988).[9]

Manipulative Techniques to the Temporomandibular Joint

Soft Tissue to Temporalis Muscle (Temporal fossa Ý coronoid process)

Procedure:

1. Stand at the head of table, with patient lying supine;

2. Ensure patient's head and neck are supported with a pillow;

3. Locate the zygomatic arch and place your finger pads 2-3 cm superior to the arch and ask the patient to alternatively clench and relax their jaw. You should feel the temporalis contracting;

4. By continuing the above, you should be able to locate the attachment area of the temporalis;

5. Using re-enforced thumbs, x-fibre the wide origin of the temporalis until you feel a change in tissue tone, i.e. the muscle should soften.

Soft Tissue to Masseter (zygomatic arch(r)angle and ramus of mandible)

Procedure:

1. Stand at the head of table, with patient lying supine;

2. Ensure the patient's head and neck are supported with a pillow;

3. Locate the zygomatic arch and angle of the mandible, and place your thumbs between them;

4. Ask the patient to clench and relax their jaw. Masseter should be palpable under the operator's thumb;

5. Once the masseter has been identified, x-fibre and/or inhibition can be carried out until you feel a change in tissue tone.

Isolytic MET Technique:

MET to Lateral Pterygoids (horizontal fibres sphenoid Ý jt capsule/ art disc of TMJ)

Procedure:

1. Stand at the side of table, with patient lying supine;

2. Ensure the patient's head and neck are supported with a pillow;

3. Support the patient's forehead with one hand and place the other, palm side (for patient's comfort), against the middle of the patient's mandible;

4. Ask the patient to open their mouth. The operator resists this action, for between 3-5 seconds (Repeat three times). Care should be taken not to force the mouth shut;

5. Reassess tone of muscle and check for reduction in mandibular deviation.

Intra-oral Techniques

Soft Tissue Inhibition to Lateral Pterygoids (sphenoid Ý jt capsule/art disc of TMJ)and Medial Pterygoids (med surface of pterygoid plate Ý med aspect of the angle of the mandible

Procedure:

1. Stand at the head of table, with patient lying supine;

2. Instruct the patient to open their mouth;

3. Using a gloved hand, palpate the pterygoids intra-orally with the index finger following the molars to the back of the mouth and beyond onto the buccal mucosa, to the medial aspect of the TMJ, just proximal to the tonsils;

4. The lateral pterygoid should be felt more by the tip of the extended index finger. Ask the patient to 'open wide'. You should feel the lateral pterygoid contract. Then turn the index finger through 90 degrees the finger pad and flex the distal interphalangeal jt, this should make contact with the medial pterygoid;

5. Inhibition to either muscle can be carried out as necessary, but ensure patient comfort at all times to prevent stimulation of the gag reflex.

High Velocity Thrust (Low Amplitude)(As attributed to G Barker DO)

Assume the patient has a right TMJ restriction. The chin deviates to the right as the mouth is opened. Soft tissue preparation has been carried out.

Procedure:

1. Stand at the head of table, with patient lying supine;

2. Ensure the patient's head and neck are supported with a pillow;

3. Rotate to the end of left cervical rotation, palpating the left TMJ with the finger pads of the index and middle fingers of the left hand. Maintain slight flexion of the C spine;

4. Place the medial border of your right hand along the raised border of the mandible and add slight compression;

5. Instruct the patient to 'open the mouth slowly';

6. As you sense movement of the mandible via proprioception of your left hand, an HVT LA is delivered via the right hand laterally and obliquely towards the side of the table;

7. This will gap the right TMJ restriction;

8. Re-evaluate TMJ motion.

Conclusion

Symptoms emanating from the TMJ and its associated structures are quite common, and are frequently sources of considerable functional disability. Therefore, following osteopathic principles, it is important to consider the structure and functional inter-relation between the structures of the head, neck, TMJ and the body as a whole, thereby diagnosing more accurately various mechanical, pathological and somatic dysfunctions and implementing appropriate treatment and management plan. Thus, it is important to ensure that the patient is kept informed of why their problem arose in the first place, and what they can do to prevent future re-occurrence through the patient information sheet.

References

1. Kuchera ML and Kuchera WA. Osteopathic Considerations in Systemic Dysfunction. 2nd ed. Columbus. Ohio. Greyden Press. 1994.

2. Moore KL. Clinically Orientated Anatomy. 3rd ed. Baltimore. Md. Williams & Wilkins. 1992.

3. Pinto OF. A new structure related to temporomandibular joint and the middle ear. Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry. 12: 95. 1962.

4. Ermshar CB. Anatomy and Neurology. 2nd ed. Morgan. Diseases of the Temporomandibular Apparatus. Mosby. 1985.

5. Farrar WB and McCarty WL. A clinical outline of the temporomandibular joint: Diagnosis and Treatment. Walter. 1983.

6. Kraus SL. TMJ disorders: Management of the cranio-mandibular complex. Churchill Livingstone. 1987.

7. Wadsworth CT. Manual examination and treatment of the spine and extremities. Williams & Wilkins. 1988.

8. Kapandji IA. The physiology of joints. 2nd ed. Vol 1. Edinburgh. Churchill Livingstone. 1970.

9. Walther DS. Applied Kinesiology. Vol 2. Head, Neck, Jaw Pain and Dysfunction – The Stomatognathic System. DC. Colorado. 1983.

Bibliography

Hartman L. Handbook of Osteopathic Technique.

Stoddard A. Manual of Osteopathic Technique.

Ward. Foundations of Osteopathic Medicine.

Stone C. Science in the Art of Osteopathy.

DiGiovanna E. Osteopathic Diagnosis and Treatment.

Greenman P. Manual Medicine.

Wernham J. Osteopathic Technique.

Sammutt E and Barnes PS. Osteopathic Diagnosis.

Chaitow L. Neuro-Muscular Energy Techniques.

Peterson & Bergmann. Chiropractic Technique.

Curl DD. Chiropractic approach to temporomandibular disorders. Williams & Wilkins. 1990.

Comments:

-

No Article Comments available