Positive Health Online

Your Country

Extract from Eat Your Weeds!

by Julie Bruton-Seal and Matthew Seal(more info)

listed in herbal medicine, originally published in issue 278 - May 2022

Introduction

Why should we eat our weeds? Because they are delicious, adding a palate of new flavours in everyday cooking. They are also nutritious and too good to waste. Weeds are actually more nutritious than most of the vegetables we grow or buy. They often have deep roots that loosen the soil and bring minerals up from far below. Weeds can help cover the soil, keep moisture in it and preserve its fertility. They offer a second crop among our other plants, for free, and are often available in the late winter and early spring when our vegetables are yet to get going. When it's time to weed, the edible weeds can be eaten. Why throw perfectly good food on the compost heap?

Weeds are strong and resilient, and can survive the vagaries of climate change better than our pampered crops. We now know that a greater diversity of plants enhances life in the soil, which in turn makes the soil more fertile and more able to hold water and to sequester greenhouse gases. Healthier soil means healthier food and healthier people.

Plants have been growing on Earth for millions of years, while we as humans are very recent arrivals. Weeds are the plants that have best adapted to our presence and activities, particularly since we adopted agriculture about 10,000 years ago. They have been our constant companions, but our relationship with them has usually been toxic and destructive.

Weeds are amazing beings that we have failed to see.

Eat your Weeds

Identify and Destroy?

Ever since humans began manipulating the environment for our own ends, we have been editing out the plants that aren’t useful to us. Over time we came to see weeds as competition for the plants we wanted to grow. We now know that plant relationships are far more complex than that, with soil life, particularly fungal networks, connecting everything in an entangled web of interactions. In modern-day chemicalized agriculture, weeds in mono-crops are often exterminated with herbicides. Gardeners also use chemicals to keep things tidy. The problem is that glyphosate (Roundup®), one of the most widely used weed killers, wipes out soil micro-organisms and damages our own vital microbiome.

We aren’t saying weeds should be left to take over the world, but believe that a better balance can be reached. We believe a lawn full of dandelions, daisies, plantain, yarrow and other plants is far more useful and interesting than a mown green grass monoculture. Weeds are free, local and sustainable, and they grow, an unused, unseen resource, without us needing to do a thing.

Identify and Harvest

With weeds, as with all wild plants you may be planning to eat, proper ID is essential. Rule number one is eat only what you are sure of. Locate a teacher who can introduce you to any unfamiliar plants. Take any opportunity you can to go on herb walks. Contact a herbalist or forager local to you, by word of mouth or (in the UK) check listings with the Association of Foragers. If you take your children on plant walks you could be giving them a gift for life.

If you see a plant often enough, and get close to it, touching and smelling, and best of all drawing it and sitting with it, you begin to know the way it carries itself, its form. In other words, you learn and intuit what the birders call ‘jizz’. Remember that when digging up a plant, including a weed, if it is not on your land you need permission. In practice people might be happy for you to collect their weeds – they might even pay you to weed for them!

Weedness and Bitterness

Bitterness as a taste is linked to good liver health, and bitter flavours stimulate digestion. Persist, and your taste buds will soon adapt and learn to welcome any extra bitterness that your weed meals give you.

We actually know very little of the chemistry of the plants we eat. Yes, there is data about the proteins, carbohydrates, fats and a few vitamins and minerals, and we generally have some idea of the calories certain foods provide. But plants and fungi (and their bacterial companions) produce a vast array of other compounds that contribute to their nutritional value and are vital for good health. Overall, weeds and wild foods are nutritionally dense, which means you will need to eat less of them to feel sated. Stick with these wild tastes because you are taking in the plant’s wildness, its survival strength.

Be aware that weeds can vary in their flavours from one place or terroir to another, and at different times of year. Experiment with this diversity.

Alexanders & Red Cabbage Slaw

Alexanders & Red Cabbage Slaw

This is a wonderful winter salad. Alexanders comes into its own when there isn’t much fresh greenery to be found. We usually blanch the alexanders to tone down the taste a little, but if your leaves are very young and tender and you like the flavour, use them raw.

For 4 to 6 people.

- Blanch a few handfuls of alexanders leaves in boiling water for about a minute. Older leaves may need a little longer. Taste to check. Drain and drop immediately into cold water.

- Mix together in a bowl:

- 1 cup chopped blanched alexanders, 4 cups finely mandolined red cabbage and 1 finely sliced apple, cut into slivers.

- Toss with about 4 tablespoons of dressing – use your favourite, or our recipe below.

- Top with a handful of toasted pumpkin seeds, and serve with more on the side.

Dressing (put in a jam jar and shake):

- 188ml (¾ cup) rapeseed oil

- 60ml (¼ cup) white wine vinegar

- 1 tablespoon orange zest

- 3 tablespoons orange juice

- 1 tablespoon lemon juice

Alexanders

Alexanders (Smyrnium olusatrum) is a tall biennial (two-year lifespan) member of the Apiaceae (carrot family). Historically, it spread from the Mediterranean and made the switch from wild-gathered plant to garden crop, and back to wild. It was both food and medicine in Classical and medieval times. Losing out to celery as a salad crop from the 16th century, it is making a comeback as a winter-foraged wild food. The best eating is when leaves and buds are young and tender; the inner stem and roots can be braised or sautéed.

What Kind of a Weed is Alexanders?

Geoffrey Grigson, writing in 1955, says alexanders is happiest and most frequent by the sea. He’s right, and sturdy stands of this vigorous and stately umbellifer proliferate in sheltered cliff and roadsides near eastern and southern coasts of Britain and Ireland, often on small islands. It is a scarce coastal species in parts of North America. Alexanders is a biennial, and the first year of its life is spent building up that stealthy root system; the second year is given over to flowering, setting seed and then dying.

Our region is more or less at the northern edge of its wild-growing range. In a 17th-century herbal like that of John Parkinson (1640), alexanders is said to flower in June and July; we often have plants blooming in March. It is an early responder to climate change, giving it competitive advantages over other plants and a nudge to us. In winter and early spring there isn’t a wealth of plants to gather, and foragers are taking the culinary hint. Alexanders is robust and can fill the ‘hunger gap’.

The History of Alexanders

The scientific and common names are clearly Mediterranean. Archaeological finds suggest it was cultivated in Iron Age Greece (c1300–700BC), and the earliest written reference is in Theophrastus, the Greek ‘father of botany’ (c371–c287BC). Its roots and shoots had become a popular potherb and vegetable by the time of Alexander the Great in the 4th century BC. The English name Alexanders could be for the emperor, or indeed for the port in Egypt that he founded and which bore his name.

The plant’s Greek name hipposelinon means ‘horse parsley or celery’, while Columella, the Roman agricultural writer (AD4–70), knew alexanders as ‘myrrh of Achaea’, the then Latin name for Greece. A contemporary of Columella, the natural history writer Pliny (AD23/24–79), called it olusatrum, or ‘black (pot)herb’, the species name Linnaeus would choose for it in the mid-18th century. Pliny thought it a herb of exceptionally remarkable nature, and noted another name, zmyrnium, a reference to myrrh, the reputed taste of the plant’s juice. There are as yet no British archaeological records of alexanders before the Roman invasion in AD43, but in 1911 seeds were found in a Roman-era well near Chepstow.

As both food and medicine alexanders continued to be a widely grown monastic plant in medieval times. By the time of the dissolution of the monasteries in the 1530s and 1540s, wild celery (Apium graveolens) was starting to be transformed by Italian agronomists into the blanched cultivated salad plant we know today. Around Europe celery’s milder taste came to be favoured over the stronger charms of alexanders, which lost popularity. In our own times alexanders is being newly appraised as a forageable weed.

Herbal and Other Uses of Alexanders

Alexanders was classified as ’hot and dry in the third degree’, and its actions were accordingly forceful. It was found to work strongly on the urinary and digestive systems, especially the seeds. The English writer William Salmon (1710) summed up: alexanders effectually provokes Urine, helps the Strangury, and prevails against Gravel and Tartarous Matter in Reins and Bladder. In modern terms, he was calling it a diuretic, which cleared the urinary system, including kidney and bladder stones.

Roman writers knew alexanders as an emmenagogue, a herb to promote menstruation. Salmon confirmed that the plant powerfully provokes the Terms; it also expels the Birth (afterbirth). That is, it was and is a powerful uterine tonic, and should still be treated with caution during pregnancy. Medieval root broths, made up of alexanders, celery, fennel and parsley, were used as purgatives for sluggish stomachs in the spring.

Alexanders was an ’official’ herb of the apothecaries in the first London Pharmacopoeia (1618). But by Salmon’s herbal nearly a century later it had gone; he noted The Shops [i.e. apothecaries] keep nothing of this plant.

It was sliding out of favour in both medicine and cookery, though there are records of alexanders root sold for urinary problems in Covent Garden market in the late 18th century.

Of course, it does not follow that because alexanders has gone out of fashion it is no longer useful as a hedgerow medicine. The virtues the old herbalists championed remain valid, and clinical experimentation is opening up some intriguing new possibilities.

One is alexanders’ essential oil. Italian researchers in 2014 found that oil from the flowers induces apoptosis, or cell death, in human colon carcinoma cells. A 2017 finding is that this oil may be effective against the protozoal parasite causing African trypanosomiasis.

How to Eat Alexanders

Alexanders is also there to be eaten! It has a strong taste for our bland modern palates, which will usually prefer celery and parsnip to alexanders and lovage. We find alexander leaves have a strong celery taste, and, like celery, quickly become stringy, so are best used young and in moderation. We use the taste to good effect to flavour salt.

They can also be used in sweet dishes and combine well with rhubarb or angelica. The roots can be cooked like parsnips but usually have a stronger taste. The simplest recipe of all is to collect the black seeds, and dry and grind them, either manually in a pepper mill or electrically in a coffee mill. Treat the seeds as a black pepper-like condiment and invite them onto your table; the urban forager John Rensten (2016) uses the seeds to replace pepper in his wild chai recipe.

Daisy Raita

Daisy Raita

This is a lovely cooling accompaniment to serve with hot spicy food or as part of a mezze.

Mix together:

- 235g (1 cup) thick coconut yoghurt

- 8g (¼ cup) finely chopped ox-eye daisy leaves & daisy leaves

- 1 clove garlic, crushed

- salt and pepper to taste

Serve at room temperature for the best flavour.

Alternatives: Try adding a little bit of finely chopped ground ivy leaves. Sorrel is also really tasty in a raita.

Daisy and Ox-eye Daisy

Common daisy (Bellis perennis) is a weed of lawns and short grass, while the larger ox-eye daisy (Leucanthemum vulgare) prefers waysides, road verges and disturbed soil. Both are edible as well as medicinal, and while the leaves of the larger daisy are popular in salads in Italy, they are under-appreciated in Britain and North America. The flowers and petals of both daisies can also be eaten.

What Kind Of Weeds are Daisies?

Children of all ages – and poets led by Chaucer – love daisies, as flowers of carefree summers when it was time to make daisy chains or garlands. Both plants had their origin in Europe and across Asia, but it is outside these native areas that they were introduced, often as garden species, and escaped to become invasive weeds, across North America, in Australasia and in parts of Africa and South America.

Daisy has a clever method for surviving in lawns: it keeps its basal leaves snug to the earth and below the level of garden mowers’ blades. Another trick is quick flowering and the fact that each flower emerges out of a stem that can be of variable height.You can find daisies in well-mown lawns flowering while hugging the ground, but when there is no mowing the flower stem will be much taller. Ox-eye adopts a different strategy, in growing tall (up to a metre or 3.3ft), and achieving maximum density of flowering blooms. A pasture or meadow in a bright summer might be overwhelmingly full of millions of the plants: a delight for the walker but a disaster for the farmer.

A mature ox-eye plant can produce up to 26,000 seeds a year. It spreads both by seeds and by rhizomes, which can replicate even from a small piece. An intriguing Anglo-French research project into meadow flowers led by Damien Hicks (2016) found that oxeye plants produced more pollen per flowerhead than any other species – no wonder ox-eye-full fields are insect-loud in midsummer. Some gardeners even welcome an outbreak of daisies in the lawn, as such a sudden appearance can be an indication of a soil deficient in lime. Daisies are rich in calcium and, as they die and decompose, their remains enrich the soil. Allowing a cycle of daisies to rebalance an over-acid soil may be a mark of wise husbandry.

The History of Daisy and Ox-Eye Daisy

In ancient Rome the first-century AD naturalist Pliny writes of daisy, but only to say briefly it is a pretty, white meadow plant. He adds, rather too cryptically: It is held that an application of it is more efficacious [i.e. herbally] if Artemisia is added.

Daisy was a Roman wound-cure herb, with bandages soaked in daisy tea deployed to treat cuts, bruises and flesh wounds from the battlefield. We have used it as an ointment for bruises and cysts ourselves, and have found that mugwort (our most common Artemisia, and included in this book) enhances the already strong healing action of daisy. It’s not clear whether Pliny is referring to military or civilian uses. In any case, daisy was well known to him, and he calls it Bellis, a name that has stuck. And no wonder – it means ‘beautiful’.

There is a minority view, espoused by the herbalist W.T. Fernie (1897), among others, that daisy is Bellis because the word also means ‘war’, since daisy was used as a healing herb in that context, much like yarrow (named Achillea after the famed general Achilles).

Daisy was a plant of the moon in classical times, dedicated to Artemis (Greece) and Diana (Rome). Ox-eye is still sometimes called moon daisy. As Christianity replaced the old gods and goddesses, so plants were renamed too. By medieval times, our two plants had new patrons: daisy had become herb Margaret and ox-eye was maudlinewort.

Herb Margaret name-checked Margaret of Cortona, a 13th-century Franciscan saint from Italy, patron of homeless people and outsiders (possibly weeds too?). She was prayed to for recovery from uterine complaints, and daisy tea was used for that purpose.

Ox-eye’s name maudlinewort referred to Mary Magdalene; the plant was also known as great marguerite, midsummer daisy and St John’s flower (St John’s day is 24 June), gypsies’ daisy, dog daisy and false sunflower.

Another identity it once had was Buphthalmum, but this name (as Buphthalmum salicifolium) now describes yellow ox-eye daisy, a European native and garden flower. The first written example of ‘daisy’ in English is recorded by the OED as around the year 1000, in a Saxon leechbook (medical recipes). ‘Ox-eye’, by contrast, first appears around 1400. Our two plant names, however, had become overly long and descriptive in both English and Latin by the time of the last great herbal in English, John Parkinson’s Theatrum Botanicum (1640).

He described 12 types of daisy, with daisy itself being the Lesser white wild Daisie (Bellis minor sylvestris simplex) and ox-eye the Great white wild Daisie (Bellis major vulgaris sive sylvestris). Modern renaming, though, has been unkind to ox-eye: once the euphonious Chrysanthemum leucanthemum (gold flower, white flower) of Linnaeus, it is now Leucanthemum vulgare (common white flower).

Herbal and Other Uses of Daisy and Ox-eye Daisy

The two daisies are often considered equivalent by herbalists; in the words of Henry Lyte (1578), there are two kinds of Daysies, the great and small. There is a difference in intensity, perhaps. Parkinson (1640) points out that the small daisy is held to be more astringent and binding than any other [of the daisies]. This astringency comes through in the taste of the leaves, daisy being less palatable as summer goes on. We have noted already that daisy, and by extension ox-eye, were wound herbs and used for uterine issues. They were given as a tea, ointment or poultice.

It is useful information that if you have daisy and yarrow in your garden (and many of us do), you have excellent healing potential at hand for wounds, bleeding and shock. Daisy tea has an old folk reputation for relieving chronic coughs and bronchial catarrhs. It has a high level of vitamin C – about the same as lemons – and is a depurative, i.e. it makes you sweat.

In some respiratory conditions, such as pleurisy, drinking hot daisy tea, while in bed, swathed in blankets, may help in breaking the fever. For blocked nasal passages the herbalist Juliette de Baïracli Levy (1974) recommends wilting daisy leaves, allowing them to cool, rolling them into balls and pushing them up the nose. She says, keep them there as long as can be tolerated. Chewing the fresh leaves can help soothe mouth ulcers.

Ox-eye is known as an antispasmodic, being used to soothe whooping cough or asthma; it is more specific than daisy for night sweats. As well as bruises (another old name is bruisewort), daisy tea can be drunk and, once cool, applied externally as a poultice or ointment for stiff neck and lumbago, various aches or stiffness.

Daisy is a wonderful pain reliever, the ‘poor man’s arnica’. Arnica (Arnica montana) is well known in self-help pain management, but the plant is endangered, expensive and has toxicity issues. Daisy is preferable in every way. Daisy tea can be used in a spray bottle as an insect repellent.

Modern research is steadily confirming daisy’s time-honoured benefits, including in wound-healing, and potential as an antioxidant, antimicrobial and antitumour aid, including for human digestive tract carcinoma (see our Wayside Medicine). Daisy has a benign reputation, and is safe for children, a fact reflected in yet another old name, bairnwort.

But take note that as an introduced alien plant in the American West and Australia ox-eye might cause contact dermatitis in sensitive skins. The hotter drier conditions in these regions may intensify the chemistry of the plant. Daisy itself can arouse allergic reactions to its pollen, but this is more likely in the related garden aster flower or chamomile.

Daisy is best avoided in pregnancy.

How to Eat Daisy and Ox-eye Daisy

A search in the herbal and cookery literature suggests that common daisy has never been a go-to wild food, even in times of famine. The taste is a little too soapy and bitter for most people, as compared with the more popular use of the tender leaves of ox-eye daisy. The leaves are available almost year round, while the flowers have a much shorter season. Commonly daisy flowers in the spring, and ox-eye flowers for about a month at midsummer, though both produce the odd flower out of season. For soups, use the youngest leaves of either plant where tenderness has not been supplanted by bitterness.

The French garden writer Jean Palaiseul (1973) likes daisy leaves as a green vegetable and stewed with meat, thus pleasing the palate and loosening the bowels at the same time. In salads both daisy and ox-eye are less bitter than dandelion leaves and can serve to modify its taste. The bright white of the flower petals is a visual delight as a salad garnish.

The urban forager John Rensten (2016) says leaves of lime tree and ox-eye form his favourite spring salad, with a dash of rosehip vinegar. The flower buds of both plants can be pickled or put fresh in a sandwich or salad, in the same manner as capers. Adding strong flavours to a daisy or ox-eye dish is a good strategy to balance the taste, as we do in our raita recipe (p68).

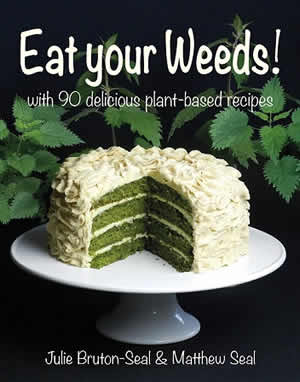

Nettle Cake

Nettle Cake

This cake is a gorgeous bright green colour. Preheat the oven to 175C/350F.

Cake

Heat gently in a pan until soft:

- 1 tablespoon vinegar, 50g (2 tablespoons) golden syrup (light treacle) , 4 tablespoons olive oil , 4 tablespoons coconut butter, and 130g (1 cup) soft light brown sugar

- Beat well and stir in 1 cup nettle purée (see p183)

- Sift 240g (2 cups) unbleached white flour and mix into the batter.

- In a cup, pour 1 tablespoon boiling water onto 1 teaspoon baking soda (bicarbonate of soda) Pour into batter and stir well. Pour batter into 2 greased and floured 20cm (8in) cake tins.

- Bake at 175C/350F for about 25 to 30 minutes, until the cake looks done and an inserted straw comes out clean.

- Cool on a rack before removing the cakes from the tins.

- Trim off the top of one of the layers, if necessary, to make it flat.

Lemon icing (frosting)

Beat to a cream:

- 250g (2 cups) icing sugar (confectioner’s sugar)

- 125g (½ cup) vegan butter or coconut butter, warmed to soften

- juice of half a lemon

- finely grated zest of half a lemon

Spread a layer of icing onto the bottom cake before placing the other cake on top. Ice the top and sides of the cake, using a spatula or a piping bag. In the facing picture I've used double the quantity of icing as a special treat.

Decorate with edible fresh or crystallised flowers, such as violets, violas, primroses or lilac.

Alternatives: We sometimes double the recipe to make 4 layers, or three layers of cake and some cup - cakes.

You can use any icing or topping that you like. If you want it less sweet, try draining thick coconut yoghurt in a jelly bag; rest this on a sieve over a bowl for half an hour to remove excess water. Add vanilla extract or other flavouring to taste and spread on the cake. Keep the cake chilled.

Nettle

Nettle (Urtica dioica) is one of our ‘desert island’ plants, offering us a pharmacopoeia of herbal medicines, compost, cordage and increasingly our food. If blackberry is our king of weeds in this book, nettle must be the emperor for its amazing variety of uses, including many recipes.

What Kind of a Weed is Nettle?

All-conquering might be the response here. Nettle (Urtica dioica) prospers in nitrogenous soils in temperate and subtropical regions. While growing to about a metre, three feet or so, tall in Eurasia and North America, species in Nepal can be double that height, while Australia and New Zealand have a nettle tree (Urtica ferox) with huge spines – a science fiction nightmare.

‘Stinging’ differentiates nettle from its cousins, the deadnettles (Lamiums in the mint family), ‘dead’ referring to their harmless hairs. In Britain we have white, pinky-red and yellow wild deadnettle species, also charmingly known as archangels. Their flowers are edible and sometimes sucked by children for their sweet nectar.

Everybody wonders why nettle needs its stings to defend it. The 20th-century naturopath Dr Vogel (1989) explained that nettle is so valuable that browsing animals would long ago have eaten it to extinction: Animals, with their instinctive knowledge of what is good for them, would not leave us even one leaf. Given this, it is good to know the sting is quickly disarmed by gentle heat, including cooking.

Nettles are wind-pollinated, which means they need no showy, fragrant flowers to attract insects. Dioica in the species name stood for ‘two houses’, giving ‘dioecious’ to describe its separate male and female plants. In reality, most nettle plants have male, female and hermaphrodite flowers. Seeing the pollen explode out of the male flowers is a wonderful, if unusual summer experience.

Its roots are another formidable weapon in nettle’s spread and dominance. The tangled yellow roots with their long and strong fibres are tough, fast-growing and go deep. You should use gloves if you want to pull them out in the garden to avoid being comprehensively stung.

The roots readily put up new shoots and later decay as the new clonal plant becomes independent. Nettles are thus perennial, if not almost immortal. The effect is a dense colony, which further crowds out competitor plants from germinating. The accessible minerals pulled up from the soil by nettle’s deep roots are a good reason nettle is acclaimed for herbal use and for eating. We have all heard about the minerals and vitamins in nettle but it is also a surprisingly good source of wild protein (20% or more by weight) and fibres.

A factor in nettle’s spread is its liking for (and by its own decomposition further adding to) nitrogenous soils, often associated with human waste.

Herbal and Other Uses of Nettle

Nettle is of the world’s major medicinal herbs, actively benefiting our respiratory, digestive, urinary and glandular systems. In this space we can hardly do justice to a treatment range from anaemia and arthritis to urinary problems and vitamin supplements. But, in brief, we can consider nettle as three medicines in one, the roots, tops and seed.

The roots, as a decoction (boiled tea) or tincture (with vodka), are known for treating prostate problems, and infections and inflammations generally.

The tops, as a tea, soup or dehydrated nettle juice powder, make an excellent spring tonic, and address anaemia and gout, high or low blood pressure, coughs and allergies, skin problems, inflammations and high blood sugar, and regulate breast milk production.

The seed, dried, ground, then mixed into a paste with honey (the herbalist's electuary), can help stop bleeding, promote urine flow, treat burns and skin problems, be a kidney support, an energiser and an aphrodisiac.

As a product nettle has another vast range of uses. It is an ancient fibre plant, making cordage or ropes, woven into a fine, soft linen or a rough military uniform (as in Austria in the First World War). It makes a dye (leaves green, roots yellow), paper, sails, fishing nets, hair rinse and shampoo, insect repellent, a rennet…

How to Eat Nettle

Nettles are nutritious. Gardeners use them to feed other plants, adding uprooted nettles to compost or steeping them in water for a strong liquid fertiliser. Nettle leaves bring fruit to ripening, and were used to pack plums. Nettles feed humans worldwide and young leaves can be eaten year-round, though tender spring leaves are best. As in tea-picking, two leaves and a bud is a motto for nettle gathering, with the bonus that in a few weeks there is a fresh harvest of new, succulent leaves.

Use rubber gloves to pick the leaves (the sting is strong in spring) or simply use scissors to cut and lift them into your bag or basket. Gathering extra allows you to freeze them for future use: blanch in boiling water for two minutes, drain and cool, then store in freezer bags.

It is worth stressing that it’s best to gather your leaves before the nettles flower. Young spring tops are best, and by cutting your nettles back you help encourage fresh growth later. Nettles in the shade will be milder and juicier than those in hot sunny places.

Nettle leaves either fresh or dried and crumbled are universally boiled as a soup or borscht.

Ray Mears and Gordon Hillman (2007) tested a nettle seed soup, but found it too burning in the mouth or stomach. We suggest sticking to the leaves. Nettle kail remains a Scottish nettle soup, eaten for Shrove Tuesday or spring in general, with nettle added to barley or oatmeal, plus onion or wild garlic. In west Yorkshire, spring or Lenten dock pudding features oatmeal, bistort and nettle leaves, again with onion or wild garlic.

Nettle porridge can be made like the soup but with extra oatmeal. Samuel Pepys’s diary from February 1661 records his enjoyment of this meal. Nettle is also an ingredient in haggis.

The old name poor man’s spinach conjures up other recipes. Adding cream in some form always enriches the overall taste of ‘greens’.

Further Information

Eat your Weeds! published March 2022 by Merlin Unwin Books. It is available to buy online or from your local bookshop. Available from Amazon.co.uk

Comments:

-

No Article Comments available