Positive Health Online

Your Country

Acid Reflux – An Osteopathic Approach

listed in craniosacral therapy, originally published in issue 293 - March 2024

Acid reflux, also known as gastroesophageal reflux disease GERD, is a condition affecting millions globally, causing discomfort and impairing quality of life. It is one of the most commonly diagnosed digestive disorders in the US with a prevalence of 20%, While conventional treatments mainly involve medications like proton pump inhibitors, Osteopathy, lifestyle modifications, and herbal remedies can offer substantial relief and long-term management. (Antunes, Aleem, & Curtis, 2024)

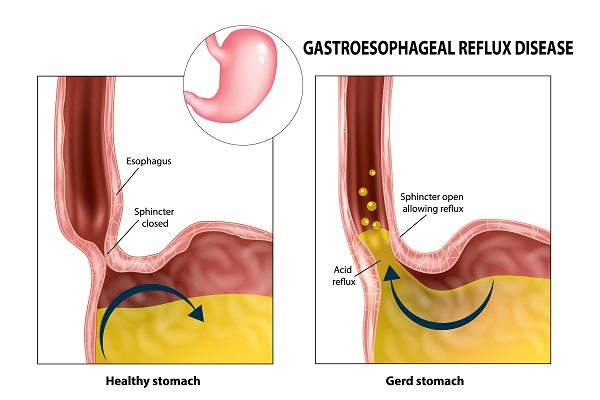

GERD occurs when the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) weakens or relaxes abnormally, allowing stomach acid to flow back into the esophagus. This regurgitation irritates the esophageal lining, leading to symptoms like heartburn and chest pain. It's vital to grasp the anatomical dynamics between the LES, esophagus, stomach, and diaphragm in comprehending GERD.

Stomach and Lower Esophageal Sphincter (Fig.1)

Osteopathic medicine emphasizes the body's innate ability to heal and maintain equilibrium. Viewing the body as a unified entity, osteopathic interventions for GERD focus on restoring proper alignment and function to digestive structures. If the structures involved are under tension and stress they start to lack the ability to adapt and compensate for life’s challenges.

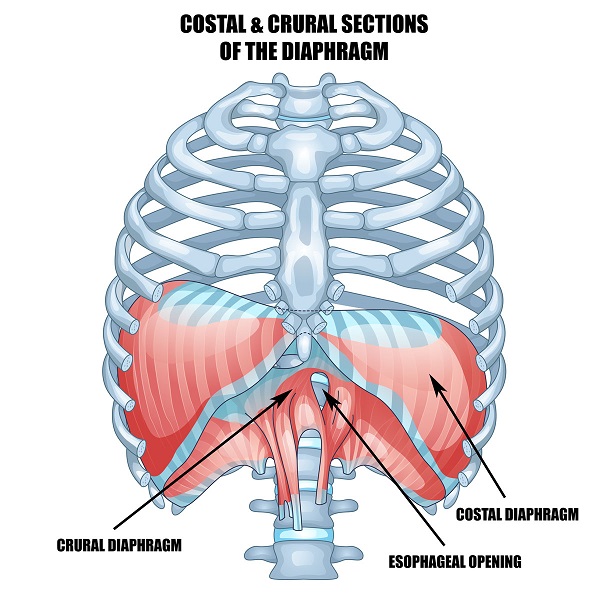

There are often structural components leading to GERD. The diaphragm muscle has a costal and crural component arranged around a central tendon (See Figure 2). [The costal part of the diaphragm has a direct inspiratory action on the lower rib cage, whereas the crural part, when the abdomen is open, has an expiratory action on the lower rib cage.] The lower esophageal sphincter passes through a diaphragmatic sphincter in the crural section of this muscle. Transient crural muscle imbalance can herald the onset of spontaneous acid reflux episodes (Pickering & Jones, 2002). An asymmetry of the trunk can result in a strain or imbalance through these structures leading to compromised function. Alternatively, there may be a compression in the whole esophagus, coming from a poor posture, where the individual slumps through the chest and gut leading to a positive pressure gradient between the stomach and the esophagogastric junction lumen .The body may well adapt valiantly to these challenges, but its ability to adapt to further stressful factors is limited. Like the ability to cope with a frequent irritant like a spicy curry late at night, the system can no longer cope, and an uncomfortable and poor night's sleep may ensue.

As an osteopath I will search for areas of tissue tension using my palpatory library to identify what feels normal for the individual and what feels under stress. Using techniques such as facial unwinding (Minasny, B. 2009), diaphragmatic work (Eguaras et al. 2019), rib mobilization, postural correction and advice I can address musculoskeletal imbalances contributing to GERD symptoms.

Anatomy of Diaphragm (Fig. 2)

As an osteopathic practitioner, I've encountered numerous cases of Acid Reflux (GERD) throughout my career. Each case presents its own unique challenges and complexities, requiring a personalized approach to treatment. One particular case stands out—John, a 70-year-old farmer, sought my help for lower back pain, but his examination revealed much more.

Upon palpation, I noticed an unusual stiffness in John's sternum, upper thoracic vertebrae, ribs, and some moderate stiffness through the diaphragm. This stiffness lacked the characteristic elastic recoil that healthy tissues should exhibit. On questioning, John revealed a daily struggle with acid reflux for the past 30 years. It could be that this predisposing stiffness in his upper thoracic had led to poor function of the upper gastrointestinal tract and strain to the lower esophageal sphincter, or years of acid reflux had caused inflammation and tissue damage, leading to the loss of healthy tissue recoil.

I knew that where there is no bounce in the tissues, there is often a lack of adaptability that leads to dysfunction. My treatment approach for John involved a gentle osteopathic technique: holding his sternum, vertebrae, and ribs into a position of ease, allowing the tissues within the thoracic cavity to unwind from tension. Additionally, I provided some gentle release of his diaphragm.

The result was astonishing – John experienced a significant return to the normal elastic recoil his tissues should express. Remarkably, on his next visit, he reported having suffered no episodes of acid reflux for the first time in 30 years. Checking in on him a year later, John remained free from acid reflux symptoms.

Reflecting on John's case, I recognize the multitude of possible aggravating and confounding factors that can predispose and exacerbate GERD in individuals. In John's case, there was a large musculoskeletal component that we were able to treat effectively in just one session.

Generally when working with a patient presenting with GERD I will work with the thorax addressing where I find tension. For example:

- Diaphragmatic Work: Osteopathic manipulation techniques can help release tension in the diaphragm and improve its mobility. By restoring proper diaphragmatic function, these techniques can alleviate pressure on the stomach and reduce the likelihood of acid reflux (Eguaras et al. 2019);

- Rib Mobilization: Addressing restrictions in the rib cage and thoracic spine can improve respiratory mechanics and reduce intra-abdominal pressure, thereby reducing the risk of GERD and hiatus hernia symptoms (Eguaras et al. 2019);

- Postural Correction: Encouraging proper posture, especially while seated, can prevent slumping and minimize pressure on the abdomen. Using cushions to support the thorax in the evening can also alleviate sagging of the esophagus and reduce abdominal organ pressure.

In addition to osteopathic interventions, I will use holistic management strategies, as they can play a crucial role in managing GERD. These strategies include:

- Dietary Modifications: Identifying and avoiding trigger foods such as caffeine, citrus fruits, tomatoes, and processed bread can help reduce acid reflux symptoms. Additionally, adopting a low-carb or ketogenic diet may alleviate carbohydrate intolerance associated with GERD. Anecdotal evidence suggests that tomatoes/tomato extract and processed bread are common triggers for GERD, while apple cider vinegar (with 'mother') can provide relief despite its acidic nature;

- Herbal Medicine: Herbal remedies like demulcent herbs (marshmallow and slippery elm) can support epithelial tissue health and reduce irritation in the esophagus. These herbs, known for their soothing properties, can be used alongside osteopathic treatments to provide comprehensive symptom relief;

- Gut Health Optimization: Testing for small intestine bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) and food intolerances can identify underlying gastrointestinal issues contributing to GERD. Probiotics may help rebalance gut flora, but caution should be exercised in patients with SIBO to avoid exacerbating symptoms. Additionally, herbal remedies mentioned above, marshmallow and slippery elm also support lower gut health and reduce irritation;

- Stress Management: Stress and anxiety can exacerbate GERD symptoms, so incorporating stress-reduction techniques such as mindfulness, meditation, and deep breathing exercises can be beneficial. Addressing stress and anxiety can also improve overall well-being and reduce the frequency and severity of GERD symptoms. Deep abdominal breathing techniques are a great way of reducing stress whilst addressing diaphragm tightness.

In conclusion, each patient requires a tailored approach, addressing not only the symptoms but also the underlying causes. By combining osteopathic principles and techniques, with personalized treatment strategies, we can achieve remarkable outcomes, restoring health and well-being to those suffering from GERD.

References

Antunes, C., Aleem, A., & Curtis, S.A.. Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. Updated 2023 Jul 3. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441938/ [Accessed [13th Feb 2024]].21:15

Eguaras, N., Rodríguez-López, E.S., Lopez-Dicastillo, O., Franco-Sierra, M.Á., Ricard, F., & Oliva-Pascual-Vaca, Á. (2019). Effects of osteopathic visceral treatment in patients with gastroesophageal reflux: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 8(10), 1738. DOI: 10.3390/jcm8101738. PMID: 31635110; PMCID: PMC6832476.

Minasny, B. (2009). Understanding the process of fascial unwinding. International Journal of Therapeutic Massage & Bodywork, 2(3), 10-17. DOI: 10.3822/ijtmb.v2i3.43. PMID: 21589734; PMCID: PMC3091471.

Pickering, M., & Jones, J.F. (2002). The diaphragm: two physiological muscles in one. Journal of Anatomy, 201(4), 305-312. DOI: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.2002.00095.x. PMID: 12430954; PMCID: PMC1570921.

Comments:

-

No Article Comments available