Positive Health Online

Your Country

Affiliative and Bonding Behavior Triggered by Threats Of Violence – The Stockholm Syndrome

by Ann Fillmore PhD(more info)

listed in psychology, originally published in issue 274 - November 2021

Foreword

“After it was over and we were safe, I recognized that they (the captors) had put us through hell and had caused my parents and fiancé a great deal of trauma. Yet, I was alive because they had let me live. You know very few people, if any, who hold your life in their hands and then give it back to you. After it was over and we were safe and they were in handcuffs, I walked over to them and kissed each one and said, ‘Thanks for giving me my life back.' I know how foolish that sounds, but that is how I felt.” [Strentz]

Courtesy psychology.wikia.org

The four hostages in the Kreditbanken robbery sympathized with their captor (right)

Knowledge to Date

Again and again, in many languages, these same emotions have been expressed by released hostages. Kirstin Ehnmark, one of the original Stockholm Kreditbank hostages insisted that – although she was hung by the neck and almost killed by one of her captors – her life was at stake because of police action. She further went on to say that she developed her strong attachment, which she described as love, to the nicer of the two captors because he “gave me my life”. She went to his trial, tried to testify in his defense, sent him flowers regularly and in general made her affection for him known publicly.[Ehnmark] After the Moloccan train episode in Holland, many of the hostages campaigned on behalf of the Moloccan cause after release.[Ochberg] Hostages have been known to shield their captors against incoming, gun wielding rescuers.[Strentz]

The behaviour, although varying in the degree of its effect in each hostage is almost identical in basic form. It has been called the Stockholm Syndrome by most students of the subject, protective affiliation by Murray Miron, traumatic bonding by Dutton and Painter, and brainwashing or collaboration by those unwilling to accept the premise that humans can be programmed to affiliate to other, very threatening humans under the correct circumstances.

Niccolo Machiavelli The Prince

Hyperlinked to https://www.goodreads.com/author/show/16201.Niccol_Machiavelli

Why this behaviour has not been recognized before is something of a puzzle since it has been well known by those in power for a long, long time. Machiavelli, early in his writings advised a Prince desirous of ruling well:

“And because men, when they are well treated by those from whom they expected harm, are more obliged to their benefactor, the common people quickly become better disposed toward him than if he had become prince with their support.”

Courtesy Wikipedia

There are those who have tried to explain its power, especially after WWII and the phenomenon of Hitler. Eric Hoffer said that such bonding was a craving to be rid of an unwanted self and in the process of ridding oneself of the despised self, the guilt and the lost faith in ourselves, we are very likely to take up a holy cause. This allows one to efface the self we want to forget. It is the frustrated, he says that are the most ready to imitate. Not long after the appearance of The True Believer in the 1950s, Stanley Schachter worked on The Psychology of Affiliation doing some group experiments to build a basis of understanding about why humans flock together. His conclusions were that mankind affiliated to avoid the anxiety which isolation brought on an individual. Such states as hunger made the need to affiliate even greater, although hunger also brought with it personal irritability at first and social disruption as it got worse.

Still, no one had found a means of detecting the process of bonding to another person or to a group. Some work was being done with monkeys and apes, but as yet human bonding was on a theoretical level. Not until the Stockholm hostage situation and its well-publicized aftermath in 1973 were there inquiries into the odd behaviour of hostages. It was not until the mid '70s and the curiosity of the law enforcement agents, mainly the FBI, that the first tries at etiologically explaining the Stockholm Syndrome were attempted. Special Agent Conrad Hassel published an article with hints at the syndrome in the Police Chief journal in 1975, John Stratton, psychologist for the Los Angeles Police Department published a descriptive article in 1977, and Special Agent Thomas Strentz of the FBI Academy wrote what has become a standard referral source, The Stockholm Syndrome: Law Enforcement Policy and Ego Defenses of the Hostage which was first published in the New York Annals of Science in 1980. Because Strentz has been in a professional position which not only allows him, but requires him, to interview numbers of hostages, including Patty Hearst, something few other researchers have the chance to do, his writing is very useful in its detailed account of the emotional reactions and similarity of behaviour of individual cases.

- He opens with a description of the phenomenon:

- “The Stockholm syndrome seems to be an automatic, probably unconscious, emotional response to the trauma of becoming a victim;”

- He goes on to explain it as a positive bond, born of the siege room, affecting both hostages and captors and uniting its victims against outsiders;

- “Like the automatic reflex of the knee, this bond seems to be beyond the control of the victim and the subject.”

Having been trained from a Freudian theoretical outlook, Strentz defines the syndrome as an ego defense involving identification out of fear and regression to a more elementary level of development where the hostage must depend on an authority figure who can kill.

Although sufficient to provide an explanation of the inception of the syndrome, the Freuds – Sigmund and Anna – had problems dealing with some of the stress victims, especially victims of violence, that later researchers have come to classify as Post Traumatic Stress Syndrome, Survivor Syndrome,[Lifton] or the Fear Process.[Fillmore] Nor does the Freudian view begin to give an understanding of the behavioural processes involved which can be extrapolated to actions of other victims who have been held under threat of violence and death, e.g. battered women.

Psychic numbing, severe anxiety, denial, nightmares and waking intrusive imagery, plus hypervigilance are some of the symptoms which can last long after the violent episode. Lifton describes all of these from his studies of survivors of Hiroshima and the Vietnam war and insists they are “defenses that block traumatic imagery and disrupt the individual's symbolization of life.”[Brett]. From Horowitz's and especially John Wilson's work we get the establishment of a science of studying disaster and war victims and the legitimization of the proper treatment for these psychological and behavioural effects, including the warning that in the severe anxiety experienced by the victims, they might come to view the therapist as another tormentor and avoid treatment.

What none of these authors address is the special feature of the Stockholm Syndrome – the protective affiliation part, probably because this is not seen in most of the victims they have studied, e.g. Vietnam vets, Hiroshima survivors. One exception would be Holocaust survivors who, in their state of powerlessness in the camps, often compulsively imitated the Nazi guards. Bettleheim] Here, then, we have the more massive effects of what we see in hostages. Lifton calls this the Survivor Syndrome.

Description of the Triggering Situation

A hostage incident starts abruptly and without warning. There is a burst of severe violence: weapons drawn, sometimes shots fired, perhaps a bystander killed, shouts and threats of death from the captors. Some hostages may be picked out as more guilty than others, these are usually men in the group. It is not unusual for a woman, or women to be chosen as the least guilty and asked to help the captors in organizing the hostages, point out those the captors might fear (e.g. law enforcement officers) or value (a wealthy public figure), Overall, the women are generally treated less harshly. Whether it is because the smaller, more compliant woman is less threatening to the captor's new territory or to a basic response which will be discussed later, it is usual for women to develop a stronger case of the Syndrome than men hostages, although this is not always true; for example on the train held by the Moloccans, in Holland, where there were both men and women captors, both men and women hostages were treated on generally equal terms – except it was a man who was chosen to be executed.

Once the initial violence is over and the situation is stabilized with the police outside and the captors in control inside, there is a measure of relief for the hostages. There is often a lot of verbal contact between the captors and the hostages. Hostage holders seem to like to tell their captive audience about their grievances and/or their cause in great detail. At this point there is usually a respite from the threats of violence except for gun waving.

Also at this point, it is not unusual for one or two of the hostages to try to get the rest of the group to help them overpower the captors. Almost without fail, the group as a whole does not allow them to try such a maneuver, insisting instead that there be no waves. Depending on the circumstances and often the ability of the negotiators, this tension-filled atmosphere will be the status quo for the duration of the incident. If a second execution does occur, it is almost always done out of sight of the other hostages and later is talked about by the remaining hostages as if it were out of their awareness, much like what happens in ancient Greek theatre.

Somewhere near the beginning of the episode, after the violence and when the organizing is being done, the Stockholm Syndrome begins to set in and is dependent on the amount of contact between the hostages and the captors. This can be of great benefit to the hostages since it also affects the hostage holders. It is much less likely for those most affected by the Syndrome to be killed. If an individual – a man – is to become a second execution victim, he will be an individual not seen as human by the captors. Assassins are trained to recognize the power of the Syndrome and are told to avoid its development by keeping the hostages isolated and/or with heads covered and mouths gagged so as to prevent them from doing and saying human things, thus making them easily disposable if need be.

Process

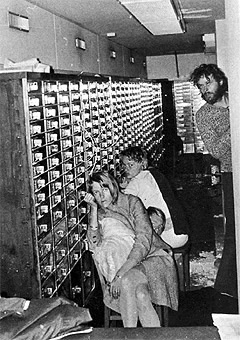

To make a jump over to the inquiry into the process of the Stockholm Syndrome or Survivor Syndrome is not easy. It must go past what students of law enforcement and psychology have so far proposed and look into behaviour and biochemistry for some of the answers. One field which has long worked with establishing methods of observing behaviour as it happens, in real time, is ethology, the study of animal behaviour. By using a checklist for bits of behaviour, e.g. grimacing, grooming and so on, a clear picture of not only behaviour but of social structure, interpersonal relationships, aggression (agonistic behaviour) and many, many more patterns can be discerned. (See Altmann's study of baboon mother-infant interactions. ) Over years of using this technique, striking similarities between social animals, birds and humans have been observed and recorded in minute detail. In reference to Stockholm Syndrome behaviours, one excellent pattern set to observe is the use of threatening behaviour by male baboons to keep their band intact and together.

Male baboons win ruling place in their troop by fighting other male baboons. Once the position is reached, the organization of the troop is maintained by constant threatening behaviour towards younger males and all females. There appear to be strict rules which, when broken, can result in swift punishment. For example, when a female lags behind the troop, the leader will run back, cuff her, and scream at her until she has returned to the troop, whereupon she immediately will do one of two things: take a submissive, sexually receptive posture or begin to groom the threatening male. Younger males, when threatened, perform the same acts and until they are ready to either leave the troop or challenge the Alpha male, they will continue these behaviours.

The maintenance of group cohesiveness is vital for the protection of the whole troop from predators. The use of agonistic, threatening behaviour is almost – and I use the word hesitantly – instinctual. It is at least a behaviour pattern taught by the mother to the infant from birth as she uses the same kind of cuffing and threats towards the infant, especially as the time for weaning approaches.[Altman] These observations of animal behaviour can be followed fairly closely by Scott's observations that as long as animal groups such as baboons are stable, there is little overt need for these threatening signals.

Let the situation change and become disorganized and without fail, baboons, as well as all other social animals, including humans become violent and destructive. It is not unusual for a male baboon taking over a troop to kill all the newborn infants in order to establish his own harem of compliant females and thus his own gene pool.

Scott points out that early humans, both male and female, were able to survive by being both timid and wary of danger. In the group, often as an isolate, there will be a man or woman who is considered to be brave and a warrior/ leader. (My emboldening) He says that when overwhelmed by circumstances, we humans are fear-biters like dogs or cats or monkeys and when pushed to the wall, act submissively. “Learning,” he continues, “based on fear and pain tends to be stereotyped, inflexible and resistant to extinction. It is easy to manipulate especially in situations of crisis.”

- Fear engenders physiological reactions;

- Scott sees that “any sort of strong emotion, whether hunger, fear, pain, or loneliness will speed up the process of socialization.” Combine this with intermittent conditions of positive and negative treatment and there occurs what is examined here: the Stockholm Syndrome, [Fillmore] also known as Protective Affiliation,[Miron] or Traumatic Bonding. [Dutton and Painter]

The last one, traumatic bonding, is suggested by Dutton and Pinter in much the same manner as this author did when presenting new theories of the transmission of child abuse from generation to generation at the International Congress on Child Abuse and Neglect in Amsterdam in 1981, that is, that such bonding is brought about by the psycho-social and behavioural environment. Dutton and Painter's paper deals with battered women, which is the most difficult victim study to build a coherent data base due to the multitudinous differences from one battered wife case to the next. It is also difficult to maintain a control group for any scientific study of this subject.

But not to say battered women don't fall into the category of victims traumatically bonded to their abuse; they do. Here though, it is often difficult, in the author's experience with battered women, to always determine the exact source of the aggressive behaviour. For the most part, it is the man who is agonistic and the in the true case of the battered woman, it will read like any hostage victim's experience or a prisoner-of-war experience with the woman desperately anxious to break away from the brutality, but trapped by the same stimuli of protective affiliation as is any hostage.

Keeping in mind Scott's theories of fear-based bonding, it would be of benefit to add Dutton and Painter's conclusions on the environmental stimuli that produce affiliative bonding:

- Power imbalance – those with no power in a relationship feel much weaker about their position than they actually are. Those in power seek to keep the control they've achieved and a change in the relation between them can cause severe disturbances, e.g. Dutton and Painter's example of the abusing husband trying desperately to regain his control once his spouse leaves or Conway's example of the de-programmed cultists looking for guidance;

- Intermittent abuse and reward or relief - Amsel points out that “intermittent maltreatment patterns have been found to produce strong emotional bonding effects in both animals and humans”, which has been the basis of behaviour/ psychology experiments for years;

- The power of bonding seems to increase when there is severe arousal, more-so if the abuse was intermittent and no other attachment object was available (Emboldening mine).[Harlow and Harlow] Infant monkeys, dogs, and other animal infants have been subjected to just this sort of treatment and the authors gave their surprised conclusions that, “instead of producing experimental neurosis, we have achieved a technique for enhancing maternal attachment.”[Harlow and Harlow] Seay found “a surprising phenomenon was the universally persisting attempts by the infants to attach to the mother's body regardless of neglect or physical punishment.”

This last observation, although it uses different terminology is virtually the same as what Scott said about socialization and strong emotions and in pursuit of the actual basis for the Stockholm Syndrome, it seems only logical to follow up with the next and latest steps in determining the amount of biochemical underpinnings to emotions and feelings, the investigations for which are bringing about a whole new way to approach behaviour and psychology.

Physiological Possibilities

Evidence has been accumulating that a large portion of our emotions are triggered by and their strength determined by the presence or absence of certain chemicals in our biological make-up. For example, falling in love, that ecstatic, euphoric state of being 'head-over-heels' and oblivious to anything but the beloved seems to depend on a combination of barely perceptible olfactory cues of sex pheromones and the very important LMRH (luteinizing-hormone) which stimulates the brain directly.[Winter and McAuliffe] This latter chemical seems to be sexual specific, but it is well known that the other sex hormones, e.g.: testosterone, adds other behaviours to the human repertoire such as aggressiveness. It seems those who are fated to fall in love again and again, that is, actually seek out such situations are addicted to the body's own production of phenylethylamine (a type of amphetamine).

On the other hand, there are those people called attachment junkies who, it has been found, attach to a person and stick regardless of their treatment by their partner and this too seems to have an addictive basis.[Carnes] This chemical is the brain's own equivalent of an opiate. When a person says they are stuck on another person, they are speaking the truth.

This whole aspect of emotional attachment has been studied by Dr Michael R. Liebowitz of the New York State Psychiatric Institute, along with his colleagues. They are so positive of their findings that they are even saying opiates such as oxytocin could be the basis of the close ties between infant and mother. Knowing what we do about abusive relationships and the way humans can be triggered to react to very differing environmental stimuli, could it be possible for, say a child, to be trained to respond to the body's release of a chemical meant to stimulate caring and have it produce something else? Perhaps there is thus a reason to believe the body's production of opiates contributed to the fanatic's adherence to a cult of cause?

Perhaps when put into a life-threatening environmental situation such as being held hostage, the victim's glands surge forth with opiates as a survival mechanism, much like attaching to the powerful parent, in which case Strentz with his dependency theory is not far wrong. That is, he could be right for the wrong reason. The behavioural mechanism which brings a hostage to the mental attitude of protective affiliation or traumatic bonding could well produce a chemical accompaniment. If we add fear to the mixture, we get another set of powerful chemicals released into the body.

Woodman found in the studies of violent social deviants that there exists a precarious balance of adrenaline (flight stimulus) to noradrenaline (fight stimulus) with the violent man having a much higher quantity of the later over a longer period of testing indicating it was part of his system. Add to this some of Schauss' work on dietary additives or deficiencies and the ideas of violence and passivity become more related to physiology than to sociology.

“(Vegetarians) have known for years,” Schauss writes, “that violent, uncontrollable rouge horses can sometimes have too much phosphorus and too little magnesium, and they give magnesium salt to stop the violent behaviour. It is no surprise that a major food source among the test group of delinquent children was soft drinks which contain a lot of phosphoric acid at as a buffering agent.” Perhaps we should consider the spread of soft drinks throughout the world and their effect on people who do not have a good dietary base to begin with, that is, not enough magnesium in their diets to overcome the effect of the phosphorus. An interesting proposition to which can also be added the deleterious effects of food dyes and sugar, phosphate and so on.

But here again, the issue of stimulus training as a starting point in the triggering mechanisms of chemicals should be addressed. Both Woodman and Schauss emphasize in their work that if there has been a harsh and/or deprived environmental background, the effects of these chemicals could be that much worse. Woodman writes, “...there could therefore appear to be the possibility that the biochemical equilibrium controlling the conversion of noradrenaline to adrenaline is influenced by the experiences of childhood and that because the hormones are interactive, the final points of balance influence personality and behaviour.”

Is this a chicken or egg question? Or is the answer that a more subtle combination of biochemical influences from birth, which might be inherited,[Mednick] in some cases predispose some individuals to violence or passivity. When psychologists, behavioural scientists, biochemists and others working in their field finally put their massive amount of new information together, we could well have the ability, as in the movie The Parallax View to pick out those humans capable of doing violence, hopefully not for the purposes of assassination as in the movie but in order to keep the wolves in the fold from attacking.

The Brave Warrior

Such potentialities for violence in some humans does not give us the solution for the behaviour except to propose that perhaps those who are the most violent are in a sense the most fearful if the socio-biochemical transmutation of a fear reaction is the violent act. Those to whom violence is done, i.e. abused boys, would comprehend no alternative but to protectively affiliate with the parent doing the violence, absorbing the psychological imperative of power winning over passiveness and the biological imperative of responding to the surges of noradrenalin as cues that a situation is calling for a violent response.

Even sociologically, boys can be violent whereas girls in present day societies, for the most part, must remain passively angry and express anger in 'deviant' social behaviour like prostitution or abusing their own children. Or as with some battered women who do violence by providing a cue to the men around her to be violent either towards her, her children or even in the outside world, the requirement being that she has found a man to fill such a need in herself.[Cade]

The brave warrior then is he who shows his fear by fighting (noradrenaline) instead of passive withdrawal or flight (adrenaline). He is the male baboon, screaming his intolerance of the outside world, close-minded to the introduction of change, of new members into his band, because any unusual and fright producing stimulus triggers him into believing he will lose control and/or possibly his life. It is Charles Manson with his tribe of women and misfit young men whom he could dominate, the terrorist whose socio-biochemical response mode is tied up with a cause and kills, or does other threatening acts much as hostage taking in order to rise to a higher level of social order within the tribe.

Courtesy: Wikipedia

Machiavelli in the Twenty-first Century

On the other side of the coin are the normal individuals who are inundated with a fear-producing situation. Their body is forced to produce changes in the norepinephrine metabolism of their brain[Fishman and Sheehan] in a way that could be an instinctively triggered reaction to fear, instinct in this case being defined as the combination of a socio/culturally ingrained behavioural ritual/pattern we call the Stockholm Syndrome or protective affiliation of traumatic bonding. If the fear induced reaction in the normal person is prolonged and severe, the Muselman phase is brought about, or at the least the Survivor Syndrome experienced by holocaust victims.[Lifton, Berger] If there is added to the socio-biochemically based reasons for the Stockholm Syndrome the triggered responses humans have to the stimuli of reciprocation,[Cialdini] plus the other modes of being influenced which involve a strong response to peer pressure and the giving or taking of affection or support by one or other of the influencing parties[Simons, Kiphis and Schmidt] then the totality of the Stockholm Syndrome is complete. Knowing how to deliberately produce such an artifact in a human is a very valuable tool for anyone seeking to educate or persuade or in the de-escalation of a violent situation. But it can just as effectively be used to produce Big Brother.[Orwell]

Therapeutic Care of Hostages

Upon release, as mentioned before, the captives often hug their captors, shake hands and promise support for them in court. Then, after the captives' numbness and denial wear off, they show signs of PTSD and, in varying degrees, the Stockholm Syndrome. It is imperative that such symptoms, including their persistent liking for their captors, be cared for by trained individuals, either individually or if possible with the hostages as a group.

The necessity for this help afterward is because, in all such cases of trauma, “a reorganization of long-standing synaptic microstructures (and) new patterns of thought and feeling may bypass or be superimposed over older ones.”[Conway] when the traumatic experiences flash back, as happens in imaging, it can be quite startling, even disturbing. Especially if the experiences replay while the subject is wide awake and busy with routine duties at the time.

In point of fact, it has been known for unaware psychologists, even psychiatrists to mistakenly diagnose schizophrenia in such happenstances.

What triggers such flashbacks in adults is most often not overtly discernible, although Terr found in her study of the Chowchilla children who had been imprisoned in a buried trailer, that the triggers were quite clear (a white church which a child had been looking at just before the captors burst into the school bus or the smell of peanut butter which is all the children had to eat during their ordeal were for them extremely powerful triggers). Without help, the hostages may experience stress reactions for years, especially from the behavioural impact traumatic bonding can inflict. It is very often the case that hostages are left to their own resources for finding treatment after the law enforcement officials are finished with their debriefing. It is also very often the case that the hostages are protected from civilian research and/or academic personnel on the grounds that information the hostages might have obtained during their captivity should be kept under security wraps.

This should be heartily objected to. It is the goal of this paper, to emphasize the need for hostages to have proper de-briefing and treatment. Secondly, for the benefit of the entire study of this particularly powerful influence on human behaviour, investigators in the field must have access both to the hostages themselves and to more detailed information about the environment which surrounded the hostages during their captivity.

Without any hesitancy, it can now be affirmed that “Violence, interspersed with intermittent relief and/or kindness, attacks on self-esteem, and an abrogation of causality for the violence, can bring about very dramatic changes in both animals and humans.”[Fillmore] And the clearest picture of this change can be illustrated by hostage situations which are especially valuable for researchers because of the detailed and often recorded, sometimes even filmed documentaries of such events taken by the negotiators and/or law enforcement officers (LEOs). Because of this chance to see an unaffected before personality, which can be attested to by both the victim and the relatives or friends, and a definite after personality change brought about by the very specific actions of the kind of intermittent violence we could not perform in a laboratory situation (as Milgram was able to do), the Stockholm Syndrome is the most distinct and pristine of the protective affiliative episodes available. They could be an invaluable source for finding the behavioural and physiological catalyst/s which produce and encourage the development of the more powerful episodes of traumatic bonding such as occur with abused spouses and abused children.

References

- Altmann J “Observational Study of Behavior) Sampling Methods. Behavior 49, pp.227-261. 1974.

- Altmann, J. “Baboon Mothers and Infants”, Harvard University Press, Cambridge. 1980.

- Amsel A. “Role of Frustrative Non-reward in Non-continuous Reward Situations”, Psychological Bulletin 55, pp. 102-119. 1958.

- Berger D. “The Survivor Syndrome: a problem of nosology and treatment” (Presentation of Research Conference, Dept. of Psychiatry, Univ. of Toronto Medical School). 1975.

- Bettleheim B. “Individual and Mass Behavior in Extreme Situations.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 38.. 1973.

- Bettleheim B. “Surviving and Other Essays” Thames and Hudson, London. 1979.

- Brett E.A. and Ostroff R.O Imagery and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder: an Overview” American Journal of Psychiatry. 1985.

- Cade B. “Family Violence: an interactional view” Social Work Today 9, p. 26. 1978.

- Carnes P. “The Sexual Addiction” CompCare Publications, Minneapolis, MN. 1983.

- Cialdini R.B. “Influence” Morrow, New York. 1984.

- Conway F and Siegelman J “Information Disease: have cults created a new mental illness?” Science Digest. 1982.

- Dutton D and Painter S L “Traumatic Bonding: The Development of Emotional Attachments in Battered Women and Other Relationships of Intermittent Abuse” Victimology 6:1-4. 1981.

- Ehnmark K “Hur jag som gisslan sag pa polisinsatsen” Nordisk Kriminalpolis. 1977.

- Fillmore A “The Abused Child as a Survivor” Paper presented to the 1981 International Congress on Child Abuse and Neglect, Amsterdam. 1981.

- Fillmore A. “Terrorism, the Threat of Violence and Policy-making” Emergency Management Review 1:5&5. 1984.

- Fischer A E “The Effects of Differential Early Treatment on the Social and Exploratory Behavior of Puppies” Doctoral Dissertation, Penn St University. 1955.

- Freud A “The Ego and Mechanisms of Defense” International Universities Press, New York. 1942.

- Freud S. “An Outline of Psychoanalysis” Norton, New York. 1949.

- Harlow H. and Harlow M. “Psychopathology in Monkeys”, Experimental Psychopathology.” M,D. Kimmel (ed): New York. Academic Press. 1971.

- Hassel C. “The Hostage Situation: Exploring the Motivation and Causes”, Police Chief. 1975.

- Hoffer E. “The True Believer”, Harper & Row, New York. 1951.

- Horowitz J.J. “Image Formation and Cognition”, Appleton-Century-Crofts, New York. 1970.

- Horowitz J.J. and Solomon G.F. “Delayed Stress Response Syndromes in Vietnam veterans”, Journal of Social Issues 31, pp. 67-80. 1975.

- Kipnis D. and Schimdt S. “The Language of Persuasion”, Psychology Today 4/ 85. 1985.

- Lifton R.J. “Death in Life”, Random House, New York. 1968.

- Lifton R.J. “On Death and Holocaust: Some Thoughts on Survivors”, The Survivor Syndrome Workshop). 1980.

- Lifton R.J. and Olson E. “The Human Meaning of Total Disaster”, Psychiatry 39, pp.1-18. 1976.

- Machiavelli N. “The Prince”, n/a Venice. 1532.

- Mednick S. “Crime in the Family Tree”, Psychology Today 3/85. 1985.

- Milgram S. “Behavioral Study of Obedience”, Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology 67, pp. 371-8. 1963.

- Milgram S. “Group Pressure and Action Against a Person”, in “Man Controlled”, Marvin, Karlins and Lewism, Andrews (eds): New York: The Free Press. 1972.

- Ochberg F. and Soskis D.A. “Victims of Terrorism”. Westview Press. Boulder, CO. 1982.

- Orwell G. “1984”, New American Library. New York. 1949.

- Schachter S. “The Psychology of Affiliation”, Stanford Press, Stanford, CA. 1959.

- Schauss A. “Diet, Crime and Delinquency”. Parker House, Berkeley. CA. 1981.

- Scott J.P. “The Process of Primary Socialization in Canine and Human Infants”, Monographs, Society for Research, New York. 1963.

- Seay B., Alexander B. and Harlow H.F. “Maternal Behavior of Socially Deprived Rhesus Monkeys”, Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology 69, pp. 345-54. 1964.

- Seligman M. “Helplessness: On Depression, Development and Death.” Freeman, San Francisco, CA. 1975.

- Sheehan D.V. and Fishman S.M. “Anxiety and Panic: Their Cause and Treatment”, Psychology Today 4/85. 1985.

- Simons M. “The Carrot and the Stick as Handmaidens of Persuasion in Conflict Situation.” 1974.

- Stratton J. “The Terrorist Act of Hostage Taking: Considerations for Law Enforcement”, The Journal of Police Science and Administration 6:2. 1978.

- Strentz T “The Stockholm Syndrome: Law Enforcement Policy and Ego Defenses of the Hostage”, Annals: New York Academy of Sciences. 1980.

- Terr L. “Children of Chowchilla, A Study in Psychic Terror”, The Psychoanalytic Study of the Child. 1978.

- Terr L. “Chowchilla's Children”. Omni. 1985.

- Wilson J. ”Post Traumatic Stress Disorders: Collected Papers”. Cleveland State University, Cleveland, OH. 1983.

- Winter R. and McAuliffe K. “Hooked on Love”. Omni 5/84. 1984.

- Woodman D.D. “Evidence of a Permanent Imbalance in Catecholamine Secretion in Violent Social Deviants”, Journal of Psychosomatic Research 23. pp 155-7. 1979.

Comments:

-

No Article Comments available